More than a year into the pandemic, mixed signals on homelessness in D.C.

By

Justin Wm. Moyer

April 29, 2021 at 4:11 p.m. EDT

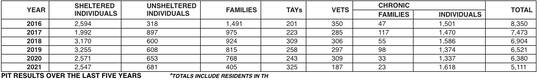

The number of chronically homeless people in the District increased by more than 20 percent last year, even as the total number of homeless residents fell by about the same amount, city leaders said Thursday.

More than a year into the coronavirus pandemic, the city’s annual count of homeless residents indicates the District has decreased homelessness among veterans and families as it lost ground among youths and those repeatedly left without housing.

The “point-in-time” count, held in January amid some of the pandemic’s darkest days, sent advocates for the homeless onto city streets to tally the number of unsheltered people. Combined with figures from shelters and other city services, the yearly census — mandated by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development — offers a snapshot of how many residents are living on the streets.

In figures released Thursday, the D.C. Department of Human Services said the number of chronically homeless people in the city rose from 1,337 last year to 1,618 this year — an increase of 21 percent compared with a year earlier.

The city’s use of the term “chronic homelessness” differentiates those without housing who have experienced homelessness for at least one year while also struggling with a mental or physical disability, or substance abuse, among other conditions.

Though the number of unsheltered individuals not considered chronically homeless remained mostly steady — 681 this year compared to 653 last year — the number of homeless people between 18 and 24 increased from 243 last year to 325 this year, or 34 percent, according Department of Human Services data.

Still, city officials noted progress in reducing homelessness since last year’s count. The total number of homeless people declined from 6,380 to 5,111, the agency said, as the number of homeless families fell from 768 to 405. The number of unsheltered veterans fell from 309 to 187.

Department of Human Services Director Laura Zeilinger said the agency viewed the data in a “self-critical way,” and would try to translate the success it has seen in fighting family homelessness into helping homeless individuals. She also said “small changes in the way we count and improvements year-over-year” might have resulted in more homeless people being included in the count than in previous years.

“We have invested in housing for every single family in our system,” she said. “For single adults, it has not been at that scale.”

The pandemic helped D.C. slash family homelessness. But a new crisis looms.

Zeilinger said a proliferation of tents on a city street can make homelessness “feel much closer to residents.” Sizable encampments beneath underpasses near Union Station and blocks from the Federal Reserve are two places where those without homes have congregated.

“Unsheltered homelessness is very visible,” Zeilinger said. “It feels like an increase with people outside in tents. … We are continuing to do relentless outreach.”

The uptick in individual homelessness comes as Mayor Muriel E. Bowser (D) has battled the problem on many fronts in the past year. An eviction moratorium has kept some people from losing their homes as the city has offered hotel rooms to those who need to quarantine. The city also replaced the dilapidated D.C. General Shelter with smaller facilities throughout the city.

On Thursday, Bowser announced the results of the point-in-time count at a news conference at the Brooks, a short-term family housing facility in Ward 3 off Wisconsin Avenue. She said that more than $300 million in federal rent relief meant that an eventual end to the eviction moratorium need not lead to an increase in homelessness.

“We talk about an impending eviction cliff,” she said. “It does not have to be that way.”

Some advocates were critical of the reliability of this year’s count.

Aaron Howe, an American University anthropology doctoral candidate who has studied encampments around Union Station and elsewhere, said unsheltered residents are “chronically undercounted.”

Since the beginning of the pandemic, encampments that are home to more than 20 people have popped up around the city, while the size of an encampment in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood has “at least tripled,” Howe said.

“It seems bad that they are talking about homelessness decreasing in Washington,” Howe said. “Things are getting bad out there and it’s only the beginning.”

Other advocates saw reasons for optimism.

Joseph Mettimano, president and chief executive of Central Union Mission, a nonprofit that runs a homeless shelter near Union Station, said it was a “credit to D.C. government” that family homelessness had declined.

Deaths among D.C.’s homeless jumped this year, including 23 who died of the coronavirus

Mettimano said Central Union has beds to spare, noting that he has seen fewer unhoused people on city streets while doing outreach — possibly because they have moved away from downtown as activity stalled during the pandemic, he said.

“As long as there is one person out there who is homeless, we need to work on that,” he said.

Many jurisdictions across the country have yet to release their 2021 point-in-time count data. Some cities, including New York and San Francisco, canceled their counts because of pandemic-related concerns.

At Thursday’s news conference in the District, 29-year-old Brittany Smith, a former resident of the Brooks, said the facility had helped bring stability to her and her three children as she awaits the arrival of a fourth.

“I’ve experienced turmoil and pain,” she said. “This place helped open up opportunities for me — to make better opportunities for me and my children.”

Justin Wm. Moyer is a breaking news reporter for The Washington Post. After a long stint as a contributing writer at the Washington City Paper, he came to The Post in 2008, becoming an editor in Outlook and for the Morning Mix, The Post’s overnight team. He became a reporter in 2015.